“Things were not adding up,” the Air Canada Airbus A320 captain told incident investigators as he explained his decision to break off an approach to San Francisco International Airport (SFO) just before midnight local time on July 7, 2017, as the A320 descended to 100 ft above Taxiway C, where four air carrier airplanes were awaiting takeoff clearances.

The captain and his first officer had failed to detect that they had aligned the A320 with the taxiway rather than with the parallel Runway 28R, where they had been cleared to land.

The U.S. National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) cited as the probable cause of the incident the crew’s “misidentification of Taxiway C as the intended landing runway, which resulted from the crewmembers’ lack of awareness of the parallel runway closure due to their ineffective review of NOTAM [Notices to Airmen] information before the flight and during the approach briefing.”

Contributing factors were the flight crew’s failure to tune the runway’s instrument landing system (ILS) frequency to obtain backup guidance, expectation bias,1 fatigue and breakdowns in crew resource management, as well as the airline’s “ineffective presentation of approach procedure and NOTAM information,” the NTSB said.

None of the 140 passengers and crewmembers was injured in the incident, and the airplane was not damaged.

Information from the A320’s cockpit voice recorder (see “A Boost for CVRs“) was not available to investigators because the recording was overwritten before Air Canada officials recognized the severity of the event, the NTSB said, adding that, if the information had been available, it would have given investigators direct evidence about events preceding the taxiway overflight.

The incident flight originated in Toronto, where the captain and first officer had reported for duty around 1640 and 1610 local time, respectively — about 10 hours before the incident. Among the information they reviewed was a NOTAM indicating that Runway 28L would be closed for nine hours beginning at 2300 that night.

The captain told NTSB investigators about a week after the incident that he had seen the NOTAM before the flight; the first officer said he could not recall whether he had seen it or whether he and the captain had discussed the information. Several weeks later, in a subsequent interview, the captain said they had discussed the matter before leaving Toronto but placed little emphasis on it because they expected to land before the closure took effect.

Before beginning the descent into SFO, the first officer obtained landing information from the automatic terminal information service (ATIS), including the report that Runway 28L was closed and its approach lights and centerline lights were out of service. The pilots told investigators that they remembered reviewing the ATIS information but did not recall whether they saw the section about the Runway 28L closure.

Air Canada procedures called for A320 pilots on the Bridge visual approach to Runway 28R to manually tune the ILS frequency into the flight management computer. This approach was the only one in the airline’s A320 database that required manual tuning for a navigational aid, the NTSB report said.

“As part of his pilot monitoring duties, the first officer would have used the multifunction control and display unit … to program required settings, but he did not enter the ILS frequency into the radio/navigation page,” the report said. “The first officer reported, during a post-incident interview that he ‘must have missed’ the radio/navigation page and was unsure how that could have happened. Also, the captain did not verify, during the approach briefing, that the ILS frequency had been entered, and neither flight crewmember noticed that the ILS frequency was not shown on the primary flight displays.”

Neither pilot could remember whether they had mentioned the closure of Runway 28L during the approach briefing, when they had discussed threats associated with the nighttime landing, the busy airspace and the fact that “it was getting late,” the report said.

The document added that, because the pilots did not remember the information about Runway 28L’s closure, “they expected to see two parallel runways while on approach to SFO and further expected that they would need to fly the approach to the right-side surface. The flight crew’s recent experience flying into SFO would have reinforced these expectations. For example, when the first officer flew into SFO two nights before the incident, the airplane used for that flight landed on Runway 28R at 2305, which was about 18 minutes before Runway 28L was closed. Also, the captain stated that he had never seen Runway 28L ‘dark’ and that none of his previous landings at SFO occurred when a runway was closed.”

When the captain saw lights across what he believed was the surface of Runway 28R, he asked the first officer if the runway was clear.

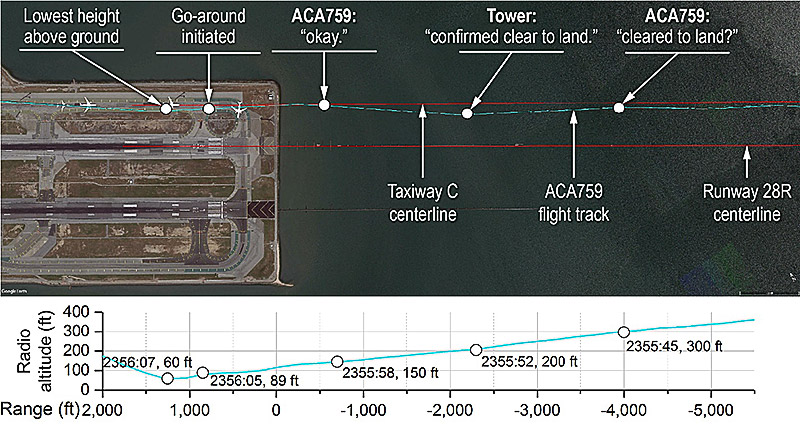

The air traffic control (ATC) recording included, at 2355:45, as the airplane descended through 300 ft, the crew’s question to the controller: “Just want to confirm, this is Air Canada seven five nine, we see some lights on the runway there, across the runway. Can you confirm we’re cleared to land?”

At 2355:52, the controller responded that “there’s no one on runway two eight right but you.”

The crew acknowledged the ATC transmission, and one second later, according to the ATC recording, another pilot asked on the tower frequency, “Where is that guy going?” The voice later was identified as that of the captain of the first airplane on the taxiway. At the time, the incident airplane was at 150 ft and about 500 ft (152 m) outside the seawall between SFO and San Francisco Bay.

At 2356:03, the airplane overflew the first airplane at an altitude of 100 ft, and the captain told ATC “he’s on the taxiway.”

The report added, “About the same time … the flight crew from the second airplane on Taxiway C … turned on that airplane’s landing gear and nose lights, illuminating a portion of the taxiway and [the first] airplane.”

At 2356:05, according to flight data recorder information, the crew of the incident airplane advanced the throttles, and the airplane’s engine power and pitch increased.

The captain later told incident investigators that, as they were preparing to land, “things were not adding up,” and the first officer told them that “something was not right.”

The report added, “As a result, the first officer called for a go-around because he could not resolve what he was seeing. The captain further reported that the first officer’s callout occurred simultaneously with the captain’s initiation of the go-around maneuver.”

ATC called for a go-around two seconds later.

From its minimum altitude of 60 ft over the second airplane, the A320 climbed to 200 ft as it passed above the third airplane and to 250 ft above the fourth, the report said.

In their subsequent interviews with investigators, both A320 pilots said that they had not seen airplanes on the taxiway.

On their second approach, the crew tuned the ILS frequency and landed on Runway 28R.

According to the report, the crew of the Boeing 737 that landed on Runway 28R four minutes before the incident airplane told investigators that the lights visible on Taxiway C “gave the impression that the surface could have been a runway.” The 737 crew used lateral navigation guidance throughout their final approach, “which mitigated the confusion we experienced from the lighting and non-normal airport configuration at SFO that night,” the 737 first officer said. He added that he had called the tower about 40 minutes after the incident to suggest that flight crews should fly an ILS approach to Runway 28R or that the tower should turn on the lights on Runway 28L to prevent confusion.

Landing at SFO ‘Lots of Times’

The 20,000-hour captain, who held an airline transport pilot (ATP) license and a type rating for A320s, had worked for Canadian Airlines from 1988 until 2000 and for Air Canada after the two companies merged in 2000. He had been an A320 captain since 2007 and said that he had flown into SFO “lots of times.” On those previous flights, both runways had been illuminated, he said.

The first officer, with 10,000 flight hours, also held an ATP license and an A320 type rating. He had worked for Air Canada since 2007. Two nights before the incident, he had been the pilot flying on a flight into SFO.

The incident flight marked the first time the two pilots had flown together.

The incident airplane had a transport-category airworthiness certificate issued in 1992 and had accumulated 82,427 hours of flight time.

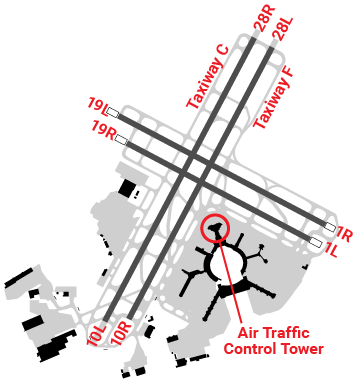

The airport, at an elevation of 13 ft above mean sea level, had two sets of parallel runways, including Runway 28R, which was 11,870 ft (3,620 m) long and 200 ft (61 m) wide. To the right of Runway 28R was Taxiway C, 12,330 ft (3,761 m) long and 75 ft (23 m) wide.

When Runway 28L was closed, it was marked with a white flashing lighted X at the approach and departure ends. The report noted that one of the tower controllers had told investigators that there had been an increase in pilot requests to adjust the lights on Runway 28R because of construction on the adjacent Runway 28L.

When the incident occurred, one controller was working all positions while a second controller was elsewhere in the building on a break. Assignments were based in part on the weather and the expected workload, the report said, adding that the amount of air traffic typically decreases after midnight.

The controller said that, initially, there was no indication that the incident airplane was not aligned with the runway. Soon afterward, when the airplane was on short final, he said, it looked “extremely strange,” and he called for a go-around.

After the incident, guidance from the acting air traffic manager said that ground control and local control positions could be combined only after 0015.

In other post-incident action, the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) in August 2017, issued Safety Alert for Operators (SAFO) 17010, “Incorrect Airport Surface Approaches and Landings,” which described best practices for landing on the correct surface, including performing a stabilized approach; using ILS, area navigation (RNAV) and other technology to support flight crew decisions; and being prepared to go around and taking that action early, “particularly during a time of confusion.”

Also after the incident, in August 2018, the FAA released a video on wrong surface landings, noting that 75 percent of such errors involve parallel runways such as those at SFO.

Recommendations

As a result of its investigation, the NTSB issued six safety recommendations, primarily intended to aid flight crews in recognizing their intended landing runway, to the FAA.

The recommendations called for the development of a system to alert pilots when their airplane is not aligned with a runway surface, and for the installation of such systems in airplanes landing at the busiest U.S. airports. In addition, another recommendation said that airport surface detection equipment (ASDE) systems should be modified to detect potential taxiway landings and alert controllers to potential collision risks.

Another recommendation called for the FAA to work with air carriers to evaluate charted visual approaches with a required backup frequency to determine autotuning capabilities of each carrier’s flight management systems and to develop autotune solutions or other alternatives for cases that currently require “an unusual or abnormal manual frequency input.”

Two recommendations called for human factors research into methods of making closed runways more conspicuous to pilots and for a human factors review of existing methods of presenting operational information to pilots, with the goal of developing guidance on best practices for presenting this information.

An additional recommendation called on Transport Canada to revise its fatigue regulations for pilots on reserve duty who are called in for evening flights that would extend into their window of circadian low.2

This article is based on NTSB Incident Report NTSB/AIR-18/01, “Taxiway Overflight; Air Canada Flight 759, Airbus A320-211, C-FKCK; San Francisco, California; July 7, 2017.” Sept. 25, 2018.

Notes

- The NTSB says expectation bias occurs “when someone expects one situation, [and] she or he is less likely to notice cues indicating that the situation is not quite what it seems.”

- Federal Aviation Regulations Part 117, “Flight and Duty Limitations and Rest Requirements: Flightcrew Members,” says the window of circadian low, when an individual’s performance is reduced during nighttime hours, runs “from 0200 through 0559 (body clock time zone).”

Featured image: © Lord of the Wings | Flickr CC-BY-SA 2.0

Video and all other images: U.S. National Transportation Safety Board