Procedures, policies and checklists are an effective way to ensure safety-related tasks are being conducted in a standardized, pragmatic way. They also are, in many cases, a regulatory requirement. But procedures are not always followed.

Procedural noncompliance, or procedural drift, has been either a primary, or contributing, causal factor in the majority of aviation accidents. The term procedural drift refers to the continuum between textbook compliance, and how the procedure is being performed in the real world.

Procedural drift is not new, but recent accidents have illuminated the ubiquity and severity of the problem, prompting the U.S. National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) to add “strengthen procedural compliance” to its Most Wanted List of transportation safety improvements in 2015. NTSB’s action largely was in response to an Execuflight Hawker HS125-700A crash on approach to Akron, Ohio, in 2015. All seven passengers and two crewmembers were killed. This article will focus on procedural drift as it applies to aviation maintenance, although the principles can be applied to any segment of the aviation industry.

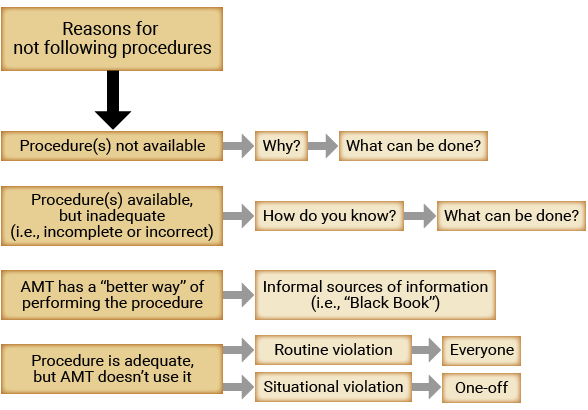

Deviations from approved procedures continue to be a leading cause of maintenance-related aircraft accidents. But why is it so hard to follow procedures? The answer to this question can range from very simple to quite complex (Figure 1).

Figure 1 — Reasons for Not Following Procedures

Source: © 2017, Robert Baron

Procedure(s) Not Available

There are documented procedures for just about all maintenance tasks. However, there are cases where either a documented procedure does not exist, or the procedure exists but is not available. In either case, it must be asked (preferably proactively rather than reactively) why a procedure is not available. Attempting a task when no written procedures are available from the manufacturer can lead to knowledge-based errors. These errors can result from the aviation maintenance technician (AMT) using “head knowledge” only, as he or she attempts to accomplish the task based on past experiences or familiarity associated with having done a “similar” task. This can lead to flawed assumptions and consequently, to a maintenance error.

In other cases, procedures may be available, but due to inadequate dissemination of information, those procedures are not accessible to an AMT. This could indicate an organizational problem. The solution for this lack of communication should not focus on ascribing blame to management or an individual, but rather on investigating the “how and why” of the problem and then working collaboratively to correct it.

Procedure(s) Available but Inadequate

In this situation, there is no problem with procedure availability; however, the procedure itself may be erroneous or flawed (that is, incomplete or incorrect). If the procedure is inadequate, the AMT might follow the procedure, only to find that an error has been made in the execution of the task.

In 2003, a Colgan Air Beechcraft 1900D crashed shortly after takeoff on a post-maintenance repositioning flight due to a reversal of the elevator trim system. Both pilots, the only two people on board, were killed. Although there were a number of links in the causal chain, one of those links included a pictorial error in the aircraft maintenance manual. Specifically, the elevator trim drum graphic was incorrectly depicted, and if someone used the graphic for guidance, it would result in a reversal of the action of the elevator manual trim system. That is exactly what happened. Compounding matters further, a functional check, which would have detected the error, was not accomplished.

In one of a number of studies that have been conducted of maintenance documentation quality, U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) researcher Barbara Kanki and her colleagues found that procedural errors, which are defined as any information-related errors involving documents, have been implicated in 44 percent to 73 percent of maintenance errors. The three most problematic areas were inspection and verification issues (34 percent), incompleteness of the documents (27 percent) and incorrectness of the documents (22 percent). Similarly, in a study of 458 NASA Aviation Safety Reporting System reports submitted by AMTs, Kanki and her colleagues found that the most frequently cited maintenance document deficiencies were missing information (48 percent), incorrect information (19 percent), difficult to interpret (19 percent) and conflicting information (19 percent). Another study, by Wichita State University researcher Bonnie Rogers and her colleagues, investigated publication change requests (PCRs) by AMTs on the types of errors found in aircraft maintenance manuals published by four manufacturers. Results showed that the majority of PCRs related to procedures found in flight controls, landing gear and powerplant systems. The highest percentage of PCRs involved procedural errors (42.5 percent), followed by language (29.9 percent), technical (16.5 percent), graphic (8.1 percent) and effectivity (with no available percentage). Common procedural errors were categorized as ordering, alternate method, check/test/inspection, caution/warning, language errors including typographical errors, grammatical errors, a need for clarification of the information, and inaccurate information within a step.

Clearly, manufacturers’ maintenance documentation may, in and of itself, be part of the overall problem related to procedural drift. However, these documentation deficiencies should not be viewed as a shift of blame from the AMT to the manufacturer. Until documentation issues such as missing information, incorrect information, difficulty in interpretation and conflicting information are resolved, it will be difficult to sell the idea of following approved procedures to AMTs on a far-reaching basis. Manufacturers and AMTs need to work together. AMTs should continue to identify and provide PCRs to manufacturers, and manufacturers should realize that their documentation can be a significant contributor to procedural drift. Keep in mind that many of the procedures in a maintenance manual have been written by engineers who may never have performed the procedure on an actual aircraft. The result is a procedure that may be unrealistic to transfer to the practical working environment. This, in turn, could account for an AMT making up his or her own way of performing the procedure.

AMT Has a ‘Better Way’

In this case, a written procedure may be available, but the AMT performs a task in a way that is different from the steps outlined in the procedure. In many cases, the AMT feels that he has a better way of performing the procedure, including skipping steps that the AMT may deem unnecessary.

In 2003, an Air Midwest Beechcraft 1900D experienced a loss of control on takeoff from Charlotte-Douglas International Airport in Charlotte, North Carolina, U.S., and crashed, killing all 21 people on board. The NTSB investigation revealed that overloading and an aft center of gravity, combined with incorrect rigging of the elevator, were causal to the accident. The incorrect rigging was attributed to an AMT skipping steps in the full rigging procedure because he deemed the steps unnecessary. A functional check was not conducted, nor was it required, at the time. A functional check would have detected the maintenance error; it subsequently became a requirement.

Some AMTs are still doing things their own way, even when the documentation is considered effective and comprehensible. A major reason for this may be a desire to take a short cut to save time on perceived “unimportant steps.” Other reasons may include complacency and norms. These are factors that can be somewhat easier to mitigate at the individual level, as compared to organizational factors such as pressure, fatigue and lack of resources, which can require a paradigmatic shift in the overall safety culture of a company.

Then there is the issue of informal sources of information, such as the “black book,” in which AMTs rewrite, or modify, procedures and store them. There are a few reasons for this. One reason is that the procedure itself is flawed, incorrect or doesn’t make sense. In this case, it is understandable that an AMT would need to modify the procedure.

On the other hand, a more ominous reason, and a more likely one, is that the AMT has figured out “a better way of getting it done.” Typically, the reason centers on time — efficiency, shortcuts or skipping steps that the AMT considers unnecessary. AMTs often deny the existence of a black book, however.

The informal source of information also can be unwritten and can take the form of tribal knowledge (procedures that are being conducted contrary to manufacturer specifications and being informally handed down from generation to generation of AMTs).

Procedure Is Adequate, but AMT Doesn’t Use It

This situation can be most problematic. These violations can fall under two broad categories: routine and situational. A routine violation (also known as a norm), happens at a collective level — “If everyone else is doing it, then why shouldn’t I?” An example of this would be AMTs not conducting a borescope inspection because “it never leaks.” This type of mindset can spread quickly, and is sometimes referred to as a normalization of deviance. On the other hand, a situational violation is typically a one-off, where an AMT does not strictly adhere to a procedure because of an unpropitious working condition (such as time pressure, fatigue or lack of resources).

In 2007, an American Airlines MD-82 experienced an in-flight engine fire requiring a turnback and emergency landing in St. Louis, Missouri, U.S. The NTSB investigation revealed that a component in the manual start mechanism of the engine was damaged when a mechanic used an unapproved tool to initiate the start of the engine while the aircraft was parked at the gate. The deformed mechanism led to a sequence of events that resulted in the engine fire, to which the flight crew was alerted shortly after takeoff. There were no injuries.

The above is an example of a typical situational violation. The term “violation” applies because the AMT has full volition of his actions and thus full accountability. This contrasts with no conscious awareness of committing an error, such as forgetting to put an oil cap back on an engine. From a disciplinary standpoint, these distinctions are important.

From the organizational level, an effective safety management system can help to identify procedural drift through mechanisms such as employee reporting, safety performance monitoring, and incident/accident investigation. But this is not a magic bullet. Much of the drift is happening clandestinely, and many of the erroneous outcomes only become known reactively, as has been exemplified in the accidents/incidents mentioned in this article. The key to reducing procedural drift is to work proactively to identify the precursors to drift, and then to address them accordingly. This begins with a healthy safety culture, which begins at the top of the organization.

Management should be very cognizant of its influences on line personnel. Company leaders may be the driving force that creates the pressure, fatigue and lack of resources that lead to errors at the AMT level, such as procedural deviations and violations. Also, keep in mind that simple exhortations such as “make sure you always do a functional check” will not be effective. Organizations need to emphasize to their AMTs, in an ongoing and holistic manner, the critical importance of following approved procedures.

From the AMT level, an awareness of the consequences of intentional procedural deviations and violations is a great start. This should be covered in human factors courses and hopefully reinforced on a continuous basis. Even then, many AMTs who succumb to procedural drift have been taught the importance of strictly following procedures. Many times, these procedural deviations are well-intentioned with no maleficence intended, and yet they wind up causing some of the worst maintenance-related accidents. Ask yourself, “If something bad happens, can I live with it?”

Keep in mind that some of the biggest problem areas are skipping steps, signoffs without verification or continuing a job without the correct tools or equipment. Also, I would be remiss if I did not make special mention of the consequential effects of skipping required functional/operational checks. Not only is this step a required component of many tasks, but it is also, in many cases, the last chance to trap any maintenance errors that may have been made in the job completion process. I estimate that at least half of all maintenance-related accidents occurred with the corresponding omission of a functional/operational check.

Bob Baron, Ph.D., is the president and chief consultant of The Aviation Consulting Group (TACG). His specializations include human factors, safety management systems, crew resource management, line operations safety audits and fatigue risk management.

Featured image: © EtiAmmos | iStockphoto